Illustrated by Himanshi Parmar

It is a common misconception that practicing “yoga” is doing postures on a ‘yoga mat’ in ‘yoga pants’ and is all about flexibility. However, as we have highlighted in the first article of our yoga series, yoga is a far deeper and more layered wisdom that provides guidance to lead a more fulfilling life. Our first article explains the different paths of yoga to get you acquainted with the yogic practice.

One of the four paths is Raja Yoga- the yoga of transforming and honing energy. Within this practice, we become aware and acknowledge our energy systems and transform them through certain practices. These practices also include ones that are more familiar like Pranayama (also known as ‘breathwork’), Asana (postures), Dharana or Dhyana (focusing our senses/meditation).

The practice of yoga that is known across the world today falls under Raja Yoga. To lead us to its ultimate potential, we must endeavor to study, practice, and embody the holistic system in its essence, which was most notably put together by Patanjali in the Yoga Sutras.

Patanjali was a sage who was instrumental in distilling the vast yogic wisdom in a simple (yet complex!) system to be guided on the path of Raja Yoga. This system has 8 limbs it is hence called the Ashtanga Yoga system- ‘asht’ means 8 and ‘anga’ is limbs. Prior to Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras, the knowledge around yogic practices was scattered and it was unclear where one must begin and progress. Through his Yoga Sutras, regarded as one of the essential texts on yoga, he prescribed a path to follow to reach the ultimate potential- eternal bliss, peace and oneness.

Yoga Sutras provide an understanding of yoga, yogic principles and techniques and ‘sadhana’ (practice) to evolve human consciousness towards a more balanced, purposeful, harmonized life.

While it is outlined as a step-by-step process, it is also cyclical. Vedic philosophy is non-linear and in the wholehearted practice of one aspect we develop concurrently in the others. If understood and practiced as prescribed, the path of yoga can be incredibly transformational for all aspects of our life and move us towards more peace and balance.

It is important to have a sense of self-awareness and humility to accept where you are on this path. The point from where we start constantly changes and checking in, being aware and mindful and honest with ourselves is incredibly important for any growth on the yogic path.

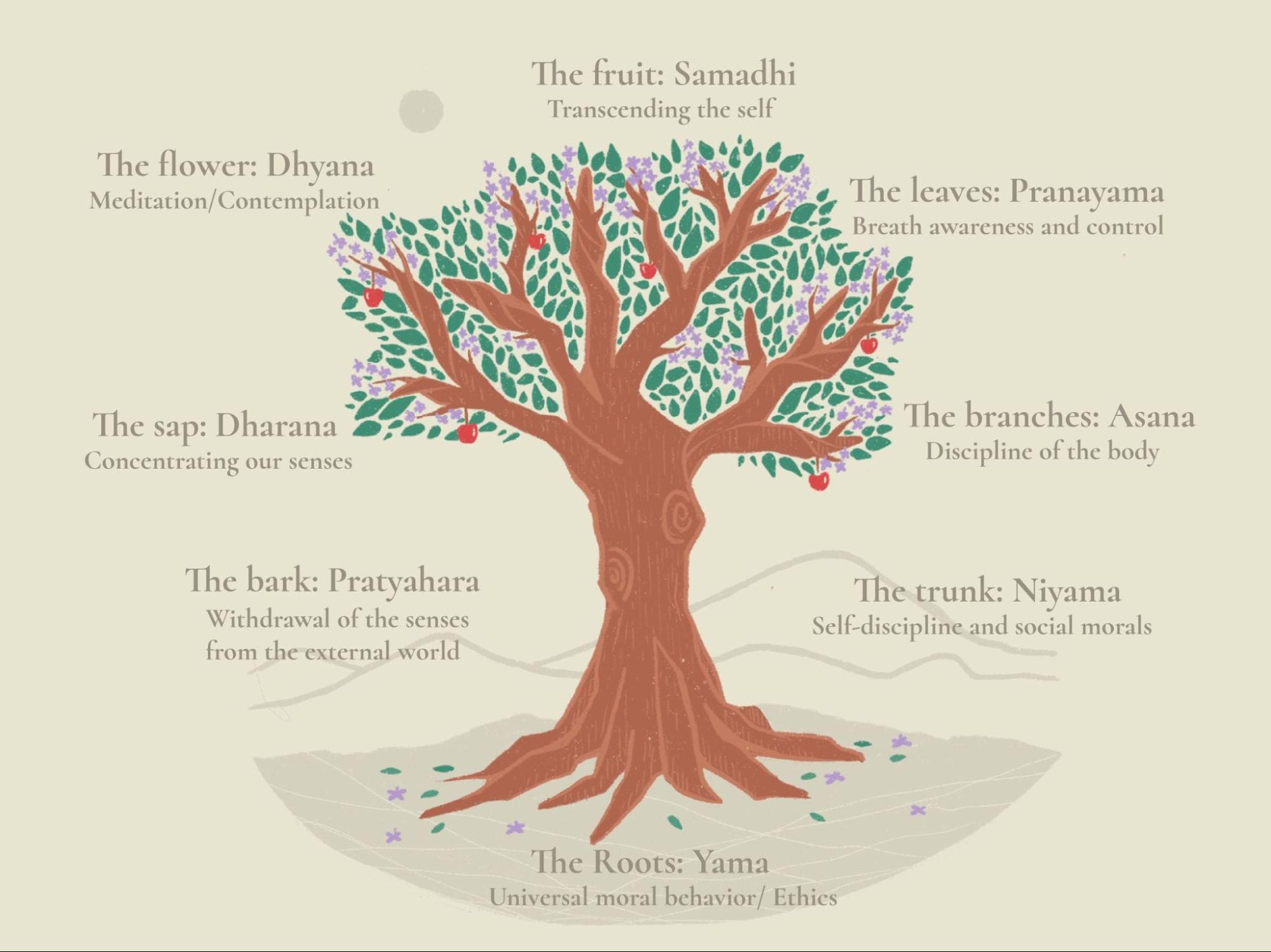

This article will use Iyengar’s beautiful metaphor of the tree linking to each limb of the yoga system, which can be found in his book Light on Yoga.

8 limb path of Ashtanga Yoga:

- The roots: Yama: Universal moral behavior/Ethics

- The trunk: Niyama: Self-discipline and social morals

- The branches: Asana: Discipline of the body

- The leaves: Pranayama: Breath awareness and control

- The bark: Pratyahara: Withdrawal of the senses from the external world

- The sap: Dharana: Concentrating our senses

- The flower: Dhyana: Meditation/Contemplation

- The fruit: Samadhi: Transcending the self, unionizing entirely with the self / eternal bliss

Yama and Niyama

Roots create our foundation and indicate how we directly relate to the world around us. They also draw nutrients and water into the plant. These Yamas are the guidelines for the way to interact with the world and what to absorb and observe.

The trunk forms the first apparent and individualistic aspect of the tree. The base and the sense of self. This is the foundation upon which we develop as individuals and these guidelines are called Niyamas.

How we relate to the world is the first step to being on the yogic path as it also informs our purpose on this path. The second step, as per the Yoga Sutras is the development of values for the self. In our last article, we spoke about how the correct approach to yoga is essential and hence the Yamas and Niyamas guide us on the path with these desired qualities.

Yamas are attributes for interacting with the world that is developed in the earliest stages of our lives. Niyamas are practices for our individual spiritual journey and growth. They are foundational moral codes and ethics outlined for us to adhere to which provide the spirit with which one approaches yoga as a way of life.

They provide us with rules for conduct, with ourselves and with others as they bring us on a path of self-discipline and ideal conduct to begin and continue our yogic journey.

Yama

- Ahimsa – non-violence/kindness/thoughtful consideration

- Satya – truthfulness always with ahimsa

- Asteya – non-stealing

- Brahmacharya – rituals to expand your purest self /moving towards truth

- Aparigraha – the absence of greed/taking only what is necessary

Niyama

- Saucha – cleanliness

- Santosa – contentment/modesty/acceptance

- Tapas – sacrifice/cleansing

- Svadhyaya – self-study

- Isvarapranidhana – surrender of the self to the Self or to God

Asana

Asana is described as the branches of the tree, on the strength of which we physically grow. The branches also physically bend in ways that we often see our own bodies bend in different Asanas so it seems like an apt metaphor!

Within the yogic view, our bodies are temples of our spirit. The practice of Asana is caring for this temple which is an essential stage of our growth- in spirit and matter.

Asana translates to ‘posture’ and is derived from the root which means ‘to sit’, ‘to stay’, ‘to be’. They are practices by which we work to unify the working of our bodies, mind and breath. Patanjali explains that Asana should have the qualities of ‘sthira’ (steadiness, alertness) and ‘sukha’(comfort).

It is not that we need to be able to meditate for hours in each posture as that definitely wouldn't have the qualities of shira and sukha. The practice of different postures helps us align our bodies, connect with our breath, initiate us on the journey of directing our minds inwards and hence maintain the seated posture or stillness required for the other stages of yoga. It is essential in any practice in yoga to steady the mind and have a single-pointed focus.

While practicing different Asanas, and stretching in 100 different ways, we come into awareness of many different parts of our bodies that everyday life may not highlight. Through this process, we come to draw our awareness and know our bodies better. We must always pay attention to what our body is communicating to us and listen to it. We come to accept ourselves and our bodies realistically for where it currently is at.

Through the practice of Asanas, we develop the habit of discipline and the ability to concentrate, both of which are necessary for the inward journey of yoga. Through regular practice, we are also able to strengthen our tolerance of the changing winds of life.

Pranayama

We come to Pranayama, the leaves of our Tree of Yoga. The lungs of the tree govern what flows into and out.

‘Prana’ means ‘that which is all around us and can be akin to ‘lifeforce’ or ‘qi’ (in Chinese terms). Prana is ‘vitality’ and what keeps the whole universe alive. The material form of which can be looked at as our breath. ‘Ayama’ means ‘to extend’ or ‘stretch which describes the action of Pranayama.

Through the practice of Pranayama, we endeavor to concentrate prana within our bodies. The more prana is outside the body, the more we are easily disturbed- mentally and physically- being susceptible to diseases and changing circumstances. One of the meanings of the word ‘yogi’ (one who practices yoga) is ‘one whose prana is all within his body’.

If prana doesn’t find sufficient space within the body, it’s because something unnecessary is blocking it and hence the practice of Pranayama is to release these blocks and have prana flow easily within the body.

The first step of Pranayama is to become aware of our breath. The practice of Asana aids us in this process. We find that a change in physical circumstances and mental state of mind affects the breath. Through the practice of Pranayama, we reverse this process to make the quality of breath influence the mind.

Pranayama techniques are designed for breath awareness and control. Once we are aware of our breath, the question arises: how do I remain conscious of my breath? The exercises of Pranayama help us concentrate on our breath to prepare for the stillness of meditation.

Different Pranayama techniques also have certain effects. For example, Kapalabhati is to ignite the fire and heat the body, Nadi sodhana is used to balance and clear the nadis (channels of the body), etc. We can practice these methods under guidance to gradually influence the state of our bodies and minds.

The first four limbs are external yoga Bhairanga Yoga.

The next four take you to the subtle levels of internal yoga Antaranga Yoga.

Pratyahara

The fifth limb of the Ashtanga Yoga system starts our journey specifically inwards and is related to the senses. It is the bark Pratyahara, which protects us from external stimuli and creates a strong barrier to concentrate and move inward.

Pratyahara translates as ‘to withdraw oneself from that which nourishes the senses’. This means that our senses stop living off the things that stimulate it and they are not dependent on them to be fed. This creates an internal environment that is more stable and has a single-pointed focus.

Pratyahara is not switching our senses off but directing them towards complete absorption in our task. When we are completely absorbed in pranayama or in reading a book, for example, we become so engrossed that our other senses completely withdraw into our task. That is Pratyahara and it happens automatically. It is the process of being the master of our senses rather than the other way around.

Example: you are sitting to practice Pranayama and you are constantly distracted by a fly buzzing on your left shoulder. This fly doesn't stay still and comes on your nose, you can hear it flap its wings. It wavers your concentration if you give it your attention and follow its flight. Pratyahara is being so engrossed in your Pranayama practice that the wayward nature of the fly is not given your attention.

Dharana

Dharana is metaphorically illustrated as the sap that nourishes our bodies, our minds drawing and concentrating our focus on what is truly important. It contains the nutrients, minerals and agents necessary for the tree to flower and fruit and reach its ultimate potential.

Dharana comes from the word ‘dhr’ which means ‘to hold’. Dharana is to hold concentration in one single direction. Through discipline, we endeavor to not be distracted and interrupted. Concentration is often wavering as our minds are easily influenced by internal or external stimuli.

In Dharana, we create the conditions for the mind to focus its attention in one direction instead of going out in many different directions[1]. It is a similar process to Pratyahara which happens automatically when we are completely engrossed in practice.

[1] ‘Heart of Yoga: Developing a Personal Practice’ by T.K.V Desikachar

Dhyana

Extended concentration (Dharana) naturally leads to meditation/contemplation- the flower and ultimate beauty of our tree- Dhyana.

T.K.V Desikachar explains in his book, Heart of Yoga: ‘During Dharana, the mind is moving in one direction like a quiet river-nothing else is happening. In Dhyana, one becomes involved with a particular thing- a link is established between self and object. Dharana is the contact, and Dhayana is the connection.”

It’s the difference between trying and simply being. While we are in Dhyana, we are simply being and fully experiencing the connection with which we are meditating upon.

Samadhi

The fruit of our practice, the ultimate within the Ashtanga Yoga system is Samadhi.

Samadhi means ‘to bring together, ‘to merge’. In Samadhi, everything that we think defines us as a person completely dissolves. Nothing is separating us, we merge and become fully absorbed together with our point of meditation.

In Dharana, we focus the mind on a single point (the breath, a sound, the moon, etc.). Through continued attention, we make a link and connection with the object of our focus which is Dhyana. In Samadhi, we completely merge with this object, engrossed entirely in its being. There is no concept of subject and object.

All these three processes can not “be done” or “be practiced” as such. When we say we are sitting to meditate, what it essentially means is that we are attempting to create the desired conditions to lead us on the path of Dharana. In the practice of Asana and Pranayama, we prepare for the state of Dharana to be followed by Dhyana and Samadhi. It is siddhi, simply given to us.

This concludes the explanation of the 8 limbs of Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras. We hope we have ignited your curiosity about the wisdom of yoga in theory and practice! Stay tuned for our next article that will provide you with resources for your onward journey to learn more about yoga and integrate the practice into your life.